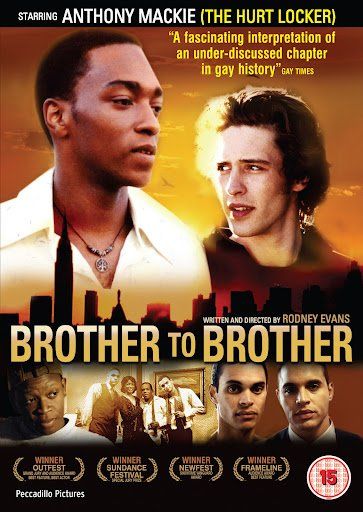

Brother to Brother Spreads Knowledge of the Queer Harlem Renaissance

In 2004 a first-time filmmaker, Rodney Evans, edited and produced a narrative film, Brother to Brother, that encompassed an extended and serious portrayal of the queer Harlem Renaissance. A graduate of California Institute of the Arts in film production in 1996, Evans had to blast through the usual challenges of bringing a first independent feature to the big screen, including losing one of his main actors and thereby having to reshoot because the production had to stop for such long periods of time while Evans raised more money. But when it appeared in 2004, it accrued a slew of accolades, including a Special Jury Prize for Dramatic Competition at Sundance. It also aired on PBS’s Independent Lens, unusual for a narrative film. What recommended it to the program that exclusively features documentaries was its meticulous research and portrayal of the queer Harlem Renaissance, subject matter that was then only known to academics and specialists.

Having read long and deeply into the Harlem Renaissance, I was impressed by the range and accuracy of Evans’ portrayal. (He also wrote the screenplay.) Though remembered through the eyes of an aging Richard Bruce Nugent, the most openly queer member of literary Young Turks challenging the art-for-racial-uplift agenda of the old guard, Evans brings to light how much and how relatively open same-sex activities were in Harlem’s working class and Bohemian wing. Both Nugent and fellow writer Wallace Thurman are depicted as far more “out there” than the repressive nature of the times would have permitted (besides which, Wallace never admitted to being gay), but such poetic license is understandable in a fiction film. The astonishing thing is that, 14 years and much more historical excavation later, Brother to Brother is still the only filmic representation of the queer Harlem Renaissance. (New York’s Black queer ballroom culture, by contrast, has spawned two documentaries, several fiction films, and a hot new TV series.)

But allow me to allay a possible misunderstanding for those who are not familiar with the film. The historical segments of Brother to Brother (cleverly filmed in black and white) are part of a larger plot in which a young Black gay artist finds inspiration and support when he befriends an aging Nugent at a homeless shelter where he works. The young artist, Perry, is hit with all of the problems faced by a Black queer teenager: thrown out of his home by a homophobic father, lonely, attacked as a fag in his Black studies class, objectified as Black sex object by his white would-be boyfriend. Perry’s got plenty to be unhappy about. But when meets Nugent, the older artist takes him on a journey through the past of the queer Harlem Renaissance from which he, presumably, finds spiritual sustenance. (We’re not shown how.) Although there’s a wash of sentimentality in the film’s (and Nugent’s) ending, Brother to Brother depicts a genuine (non-sexual) relationship of growing affection and mentorship between an older and considerably younger Black gay man. That’s rare to see on screen.

One of the great virtues of

Brother to Brother, when looked at through the lens of Black queer portrayals, is how vivid and individualistic its characters are. (No lesbians, of course.) Nugent and Thurman were remarkable, multifaceted men. They could not be flattened to stereotypes. (Outside the frame of the film, Thurman was in fact self-hating on a number of levels -- in the closet, too Black, acutely aware that his writing talent didn’t match his ambition—and drank himself to an early death at the age of 32.) The closest we have to a stereotype is the young Perry who suffers the generic miseries enumerated above, but Anthony Mackie’s acting gives him individuality.

How good is

Brother to Brother as a movie? Pretty good. Rotten Tomatoes gives it an aggregate critics’ rating of 77%. It’s not the masterpiece that is Isaac Julien’s

Looking for Langston, but it’s a real testament to the ambition and determination of a newly-minted Black queer filmmaker. For that alone he earns our respect. And he has blazed a path the others still have not gone down.

Recent Posts

SHOGA FILMS is a 501(c) (3) non-profit production and education company. We create multimedia works around race and sexuality that are intended to raise awareness and foster critical discussion.

Contact Us

All Rights Reserved | Shoga Films

Stay Connected

Thanks for subscribing!

Please try again later.